Carolyn Y. Johnson

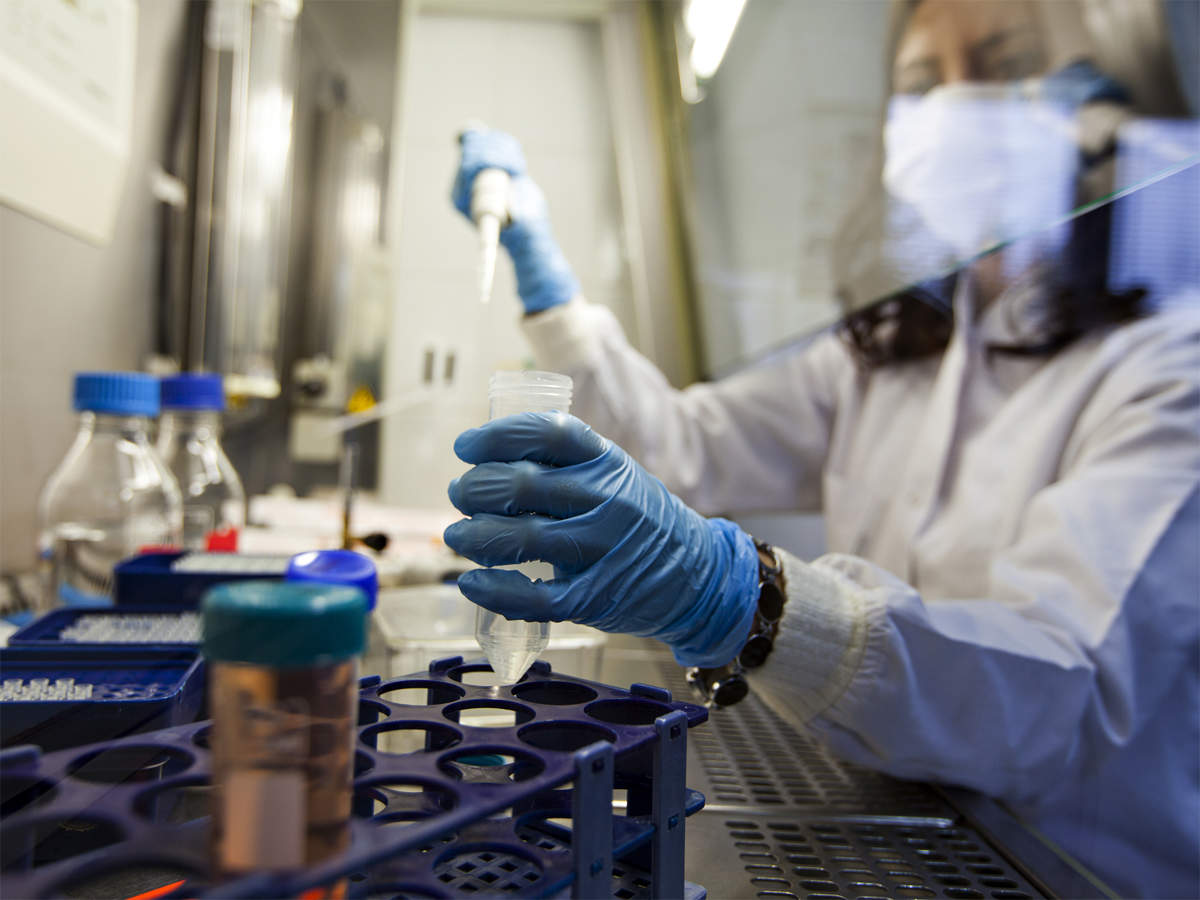

Ian Haydon, a healthy 29-year-old, reported to a medical clinic in Seattle for a momentous blood draw last week.

“Oh yeah,” said the nurse taking his blood. “That is liquid gold.”

Haydon is an obscure but important participant in the most consequential race for a vaccine in medical history. In early April, he was among the first people in the United States to receive an experimental vaccine that could help end the coronavirus crisis. He volunteered to be a test subject knowing about the risks and unknowns, but eager to do his part to help end the worst pandemic in a century.

Scientists at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., will study blood from Haydon and others for signs that the vaccine triggered an immune response to a pathogen they have never encountered. It would be the first, preliminary signal that the vaccine could provide immunity to covid-19, the disease caused by the virus, that has claimed more than 200,000 lives.

A coronavirus vaccine has become the light at the end of a very long tunnel, the tool that will bring the virus to heel, allowing people to attend sports events, hug friends, celebrate weddings and grieve at funerals. The goal to deliver a vaccine in 12 to 18 months, often repeated by the nation’s top infectious disease scientist, has become the one reassuring refrain during briefings on the crisis. The White House put together a task force called Operation Warp Speed to try to move even faster, making hundreds of millions of doses ready by January.

With at least 115 vaccine projects in laboratories at companies and research labs, the science is hurtling forward so fast and bending so many rules about how the process usually works that even veteran vaccine developers do not know what to expect.

Scientific steps that typically take place sequentially over years — animal testing, toxicology studies, laboratory experiments, massive human trials, plans to ramp up production — are now moving in fast-forward and in parallel. Experts keep using the word “unprecedented.”

It’s a thrilling time in vaccine science, but also an unnerving one.

U.S. regulators are firm in that they will not sacrifice safety for speed, but some ethicists raise concerns about “pandemic research exceptionalism,” in which the demand to speed a vaccine to market could come at the expense of evidence and fuel the powerful anti-vaccine lobby.

“The 26 years it took us to make the rotavirus vaccine is pretty typical. If it’s 12 to 18 months, you’re skipping steps,” said Paul Offit, who developed a vaccine for rotavirus, which causes deadly diarrhea in infants and children. “Is that a little risky? Yes it is, but so is getting infected with the virus.”

Science at ‘lightning speed’

On a weekend in early January, scientists at Inovio Pharmaceuticals, a biotech company outside of Philadelphia, began designing a vaccine for a mysterious pneumonia that didn’t even have a name. They, like other teams around the world, used the genetic blueprint of the novel coronavirus, shared online by Chinese scientists, as their guide.

It took about three hours to design the vaccine, said Joseph Kim, the chief executive of Inovio.

Scientists at NIH had been in talks about partnering with a Massachusetts biotechnology company, Moderna, and immediately began designing another vaccine candidate. By the end of the month, it was in production in a factory filled with robots in a suburb south of Boston.

With an array of promising vaccine technologies fueled by early scientific openness, dozens of vaccine efforts kicked off blindingly fast in dozens of countries.

“Then, the tough work began,” Kim said.

Designing a promising vaccine is, in some ways, the easy part. Showing that it is safe and effective, and then scaling up production can takes years, or even decades. Researchers are now trying to compress that timeline in ways they never have before, against a type of virus they have never successfully quelled. In some cases, they are also harnessing technologies that have never been used in approved vaccines. In contrast, scientists develop a new flu vaccine each year, an effort that is more of a “plug and play” situation, where a time-tested basic platform can be redirected to fight new flu strains.

“It’s another reason for better preparedness,” said Barney Graham, the deputy director of the Vaccine Research Center at the National Institutes of Health, pointing out that his lab had developed a vaccine for MERS, a related coronavirus, but only got it through mouse studies. “If we’d taken at least two to three vaccine concepts through early phase clinical trials on MERS, we might have a better idea on what to focus on for this SARS coronavirus — so instead of working with 115 different vaccine ideas, we might be working on five.”

Scientists at Oxford University have announced the most aggressive timeline, with plans to make their vaccine — which depends on a weakened cold virus that typically infects chimpanzees — available in the fall.

Moderna and Inovio are developing vaccines that ferry two different types of genetic material into cells to train the immune system to recognize the distinctive “spike” protein on the surface of the coronavirus. A Beijing company is trying an inactivated virus. Giant pharmaceutical companies, flush with government funding, are turning their vaccine platforms toward coronavirus. Researchers at Texas A&M University are repurposing an existing tuberculosis vaccine to see if it can prevent deaths or severe illness. (Courtesy: The Washington Post)