The United States’ approach to international trade, particularly under the “America First” doctrine, reflects a prioritization of domestic manufacturing, job creation, and trade balances over multilateral cooperation. However, in an increasingly interconnected world, rigid adherence to self-interest can be self-defeating. Global problems often require collective solutions, writes former IAS officer V.S.Pandey

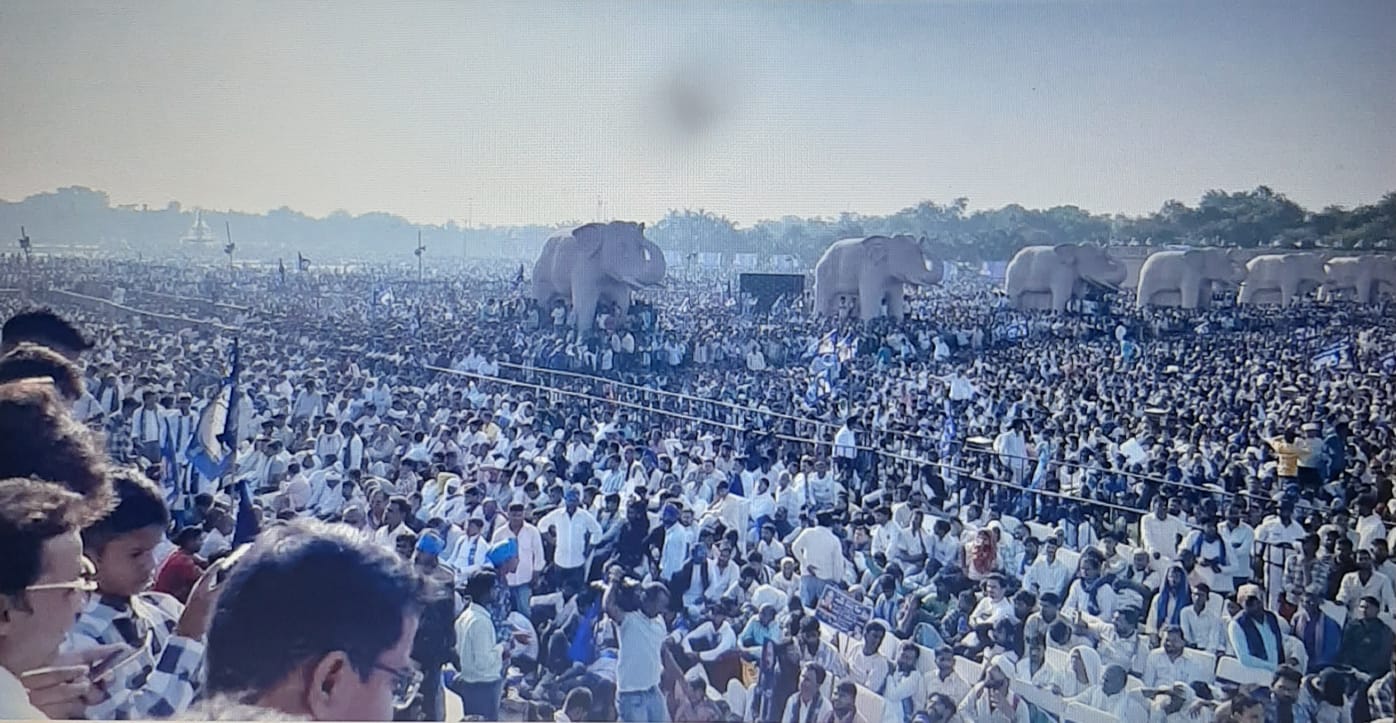

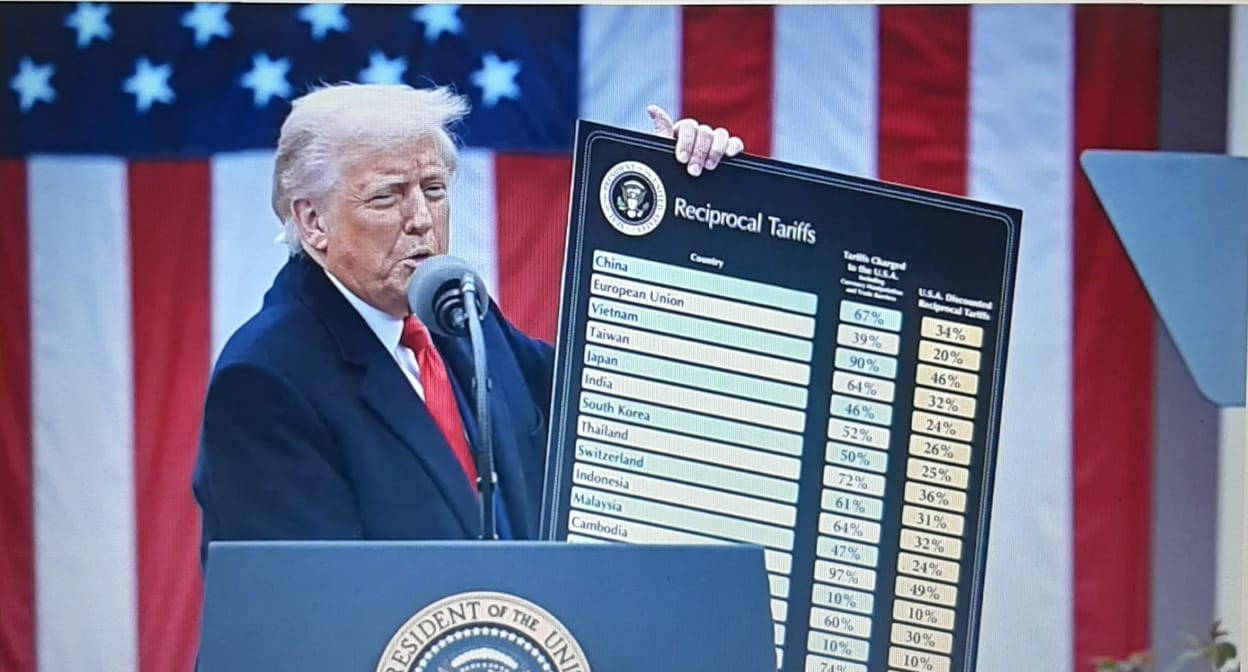

Global trade is in complete disarray due to the tariffs imposed by the current US administration. Nations are absorbed in trying to negotiate their way out of this mess. The initial stock market slump has given way to some upward movement in stocks, thus mitigating the situation to a limited extent. The salient question still is -Who is going to benefit and who will lose out in the bargain. Most of the countries impacted by the US tariffs are already on the negotiating table placating the US which “wants to undo the past mistakes” of its earlier administrations which had lead to massive trade deficits running into several billions of dollars.

In the realm of international relations, the primacy of national interest is a foundational principle that guides the foreign policy of virtually every state. Whether in matters of diplomacy, trade, security, or cooperation, nations act primarily to advance and protect their own interests. This concept, often rooted in realism—a dominant school of thought in international relations—asserts that states are rational actors motivated by self-preservation, power, and economic advantage. While idealism promotes moral values and international cooperation, realpolitik underscores a more pragmatic view: that a country’s interest must come first.

The concept of national interest encompasses everything a country considers essential for its survival and prosperity. In a competitive international system, these interests are often pursued with single-minded focus, sometimes at the expense of ethical considerations or the needs of other countries. Despite ideological rhetoric, their actions are driven by the need to preserve geopolitical influence and prevent the expansion of the other’s power. This behavior illustrates how national interest often trumps universal principles like democracy or human rights when they conflict with strategic goals.

From this perspective, it becomes rational and even moral for a state to prioritize its own interests. Leaders are accountable to their citizens and are obligated to act in ways that enhance national welfare. Sacrificing a nation’s interest for global causes, unless profiteering from those interests, can be politically risky and economically damaging.

Throughout history, especially recently ,in the heyday of imperialism and the carving of the globe into colonies – the principle of national interest ruthlessly guiding foreign and trade policy was evident. The United States’ approach to international trade, particularly under the “America First” doctrine, reflects a prioritization of domestic manufacturing, job creation, and trade balances over multilateral cooperation. However in an increasingly interconnected world, rigid adherence to self-interest can be self-defeating. Global problems often require collective solutions.

The dilemma of choosing between righteous action versus the expedient one, has always existed and decisions taken in this regard have defined the character of leaders and the trajectory of the nation. The culture of expediency has harmed civilization egregiously and led to innumerable wars and bloodshed. An excellent example to illustrate happened on 13 June 1947,when Einstein wrote a four-page letter to Nehru, appealing to Nehru to stand with Israel . Einstein praised him as a “consistent champion of the forces of political and economic enlightenment”, and exhorted him to rule in favor of “the rights of an ancient people whose roots are in the East”. Einstein pleaded for “justice and equity”, adding that “long before the emergence of Hitler, I made the cause of Zionism mine, because through it, I saw a means of correcting a flagrant wrong”

Nehru’s response to Einstein’s letter reflected his deep moral dilemma. Nehru did not hedge this, and acknowledged that India’s policy was dictated by realpolitik, despite moral posturing. Nehru wrote that national leaders, “unfortunately”, had to pursue “policies… essentially selfish policies. Each country thinks of its own interest first… If it so happens that some international policy fits in with the national policy of the country, then that nation uses brave language about international betterment. But as soon as that international policy seems to run counter to national interests or selfishness, then a host of reasons are found not to follow that international policy. This was Nehru’s explanation for India voting against the partition of Palestine and the creation of a Jewish State. The compelling reasons were India’s own partition and India’s large Muslim population which, like other Muslims elsewhere, was instinctively pro-Palestinian, seeing the issue as an Islamic cause, and India’s need for support from inter alia Arab countries, in the impending 1948 war over Kashmir with Pakistan. Nehru went on to argue in his letter: “I confess that while I have a very great deal of sympathy for the Jews, I feel sympathy for the Arabs also… I know that the Jews have done a wonderful piece of work in Palestine and have raised the standards of the people there, but one question troubles me. After all these remarkable achievements, why have they failed to gain the goodwill of the Arabs? Why do they want to compel the Arabs to submit against their will to certain demands “? Eventually, India officially recognized the State of Israel on 17 September 1950. At the time, Nehru said: “We would have long ago, because Israel is a fact. We refrained because of our desire not to offend the sentiments of our friends in the Arab countries.” Though Einstein could not convince Nehru immediately, despite the latter’s deep admiration for the great scientist, his letters did play a crucial role in convincing Nehru finally.

Ultimately, the statement that “in international relations, one’s country’s interest comes first” is a reflection of political reality. While idealism and moral leadership have their place, the driving force behind most foreign policy decisions remains national interest. The challenge for today’s leaders is to pursue those interests responsibly, recognizing that in many cases, cooperation and mutual benefit are not just altruistic ideals but practical strategies for long-term national success. In a world where global and national interests are increasingly intertwined, smart statesmanship requires aligning the two as much as possible. World leaders need to act prudently in today’s world and bridge -not enlarge – the widening gulf between various groupings and countries. Chomsky resonates, States are not moral agents, people are , and can impose moral standards on powerful institutions. We ,the people must act to fulfil this acute need.

(Vijay Shankar Pandey is former Secretary Government of India)